|

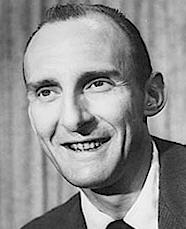

Chuck Thompson, Voice of the Baltimore Orioles, Diesby Ed Waldman, Baltimore Sun

Mr. Thompson, known for his catch phrases "Ain't the beer cold!" and "Go to war, Miss Agnes!" came to Baltimore in 1949 to broadcast the games of the International League Orioles and never left. "He was a joy to work with," said Vince Bagli, Mr. Thompson's longtime announcing partner with the Colts. "He was the best who ever worked in this area. Other than [for] Brooks Robinson, the best ovation [at an Orioles game] was when they said that Chuck Thompson was going to Cooperstown." Said former Colt Tom Matte, now a radio analyst for Ravens games: "In my opinion, he was probably the greatest announcer I've ever known. He had a class all to himself. He had the greatest voice in the world." Mr. Thompson died at 8:17 a.m. yesterday. He was stricken shortly after 7 a.m. Saturday at the Mays Chapel home he shared with his second wife, Betty, and was rushed to Greater Baltimore Medical Center, according to his brother-in-law, Fred Cupp. Craig Thompson told reporters at GBMC yesterday that his father died "very peacefully, in his sleep," with his family by his side. "This city of Baltimore has lost a good friend," Craig Thompson said. "And the sports media has lost one of the greatest voices of all time." He asked that the news media respect the family's privacy and said it will be releasing more information in the coming days. Mr. Thompson's health had declined in recent years. In 2000, he was forced to stop calling play-by-play on Orioles games part time because he suffered from macular degeneration, which made it impossible for him to read documents or follow the ball. He also suffered from some dementia and short-term memory loss, his brother-in-law said. "He was without a doubt a giant in the business," said Jim Hunter, a current Orioles announcer. "As far as I'm concerned, he'll always be the voice of the Orioles. He was Mr. Oriole. You could even argue as much as Brooks [Robinson] and Cal [Ripken Jr.] were." Veteran sportscaster Ted Patterson featured Mr. Thompson in two of his books, The Golden Voices of Baseball and The Golden Voices of Football. "He was a throwback to an era when the broadcasters painted the pictures," Mr. Patterson said. "And he was tremendous at it." In 1993, Mr. Thompson, an ASA member for many years, received the National Baseball Hall of Fame's Ford C. Frick Award, which, while not signifying induction into the Hall, is the highest honor a baseball announcer can receive. "It was well-deserved," Mr. Bagli said. "It was overdue. But he never had the national profile. He never wanted to leave here. He had chances. But he loved Baltimore." Said former Orioles manager Earl Weaver: "He did his job, he did it every day, and he did it as well as anybody could do it. He's going to be remembered, and there are going to be a lot of tapes that will still be played of some of Chuck's calls during all those fantastic years that the Orioles had." To the day of his death, Mr. Thompson's voice could be heard on radio in commercials for a number of local companies. Mr. Thompson was born in Palmer, Mass., on June 10, 1921. His family moved to Reading, Pa., in 1927, just before he began first grade. While in high school, Mr. Thompson worked as A singer with dance bands, earning $1 a night for singing eight songs and $5 for a New Year's Eve gig. He broke into broadcasting in 1939, calling the games of Albright College for WRAW radio in Reading. He earned $5 a game. He was inducted into the Army on Oct. 5, 1943, and after 17 weeks of basic training was sent to Europe aboard the Queen Mary. A sergeant, he fought in the Battle of the Bulge. After an honorable discharge in August 1945, Mr. Thompson resumed his broadcasting career with WIBG, a radio station in Philadelphia. Besides being a fine announcer, Mr. Thompson's career was marked by being in the right place at the right time. He broadcast his first major-league game in 1946 when the Philadelphia Phillies' regular announcers were delayed getting to the radio booth because they had been honored on the field between games of a doubleheader and the elevator operator wasn't there to bring them back. "The next thing I knew, Whitey Lockman was coming to the plate to start the second game and I just started talking," Mr. Thompson told The Sun in 1993. When the veteran announcers finally made it back, a station executive instructed them to "sit down and work with the kid," Mr. Thompson recalled. Then, in 1948, Mr. Thompson was supposed to do color commentary on the radio broadcast of the Navy-Missouri football game from Baltimore. The play-by-play announcer got sick, and Mr. Thompson had to do the game by himself. A few days later, the Gunther Brewing Co., which owned the broadcast rights to the International League Orioles, offered him the job of replacing Bill Dyer. To sweeten the offer, Gunther threw in the job of broadcasting the pro football games of the All-America Football Conference Colts. It was the start of a wonderful love affair between Mr. Thompson and Baltimore. "He got to Baltimore and became a legend in the town," Mr. Hunter said. "If you were a fan, you followed your favorite team with Chuck behind the mike, and that includes the Orioles and Colts. And that's rare for someone to be identified so strongly with two teams." When the St. Louis Browns moved to Baltimore in 1954, the National Brewing Co. acquired the team's broadcast rights, and Mr. Thompson was temporarily out of a job. But before the next season, an agreement was struck allowing Mr. Thompson to call Orioles games. In 1957, a dispute between National Brewing and Gunther Brewing, which was still his employer, forced Mr. Thompson to leave the Orioles to call Washington Senators games. During those years, he was also hired by NBC to call its Game of the Week telecast. It was during the 1960 World Series between the Pittsburgh Pirates and New York Yankees that Mr. Thompson made an error that, in his 1996 autobiography, he called "easily the most embarrassing moment of my career behind the microphone." Bill Mazeroski hit a home run in the bottom of the ninth inning of the seventh game to win the Series for Pittsburgh. The homer, off pitcher Ralph Terry, made the final score 10-9. But Mr. Thompson said the Pirates' second baseman had gotten the hit off Art Ditmar and announced the final score as 10-0. Given a chance to correct the error on a souvenir record the Pirates produced, Mr. Thompson declined. "I figured it had gone on the air that way, so it wouldn't be honest to change it," he wrote. In 1962, Mr. Thompson returned to broadcasting the Orioles. Mr. Cupp said his brother-in-law's loyalty to National never wavered. Once, while taking former Orioles star Boog Powell out for crabs at Bo Brooks, Mr. Thompson told the manager he wanted "the biggest crabs that they had," Mr. Cupp recalled. "The manager came out with the crabs in an American Beer box," he said. "An American Beer box. You know how Chuck was with National Brewery. He said, 'I'm not going to take those crabs. No way.'" Mr. Thompson called Orioles games until his first retirement in 1987. In 1991, he came back to work part time and continued on a limited schedule until 2000. "He was such a gentleman," said Jeff Beauchamp, vice president and station manager of WBAL radio, Mr. Thompson's longtime employer. "I don't know if he had any enemies. He was never too busy to shake a hand or sign an autograph. And that's why he had earned that respect around the community. "He had a distinctive style. It was a very rich style that was familiar to Baltimore, and people felt comfortable with him. He was someone they trusted." Another moment in the national spotlight for Mr. Thompson came in 1958, when he was part of NBC's telecast of the National Football League championship, won by the Colts in overtime against the New York Giants and dubbed by many as "the greatest game ever played." Mr. Thompson shared the booth with Chris Schenkel. The two announcers flipped a coin to decide who would do the play-by-play for which half, according to Mr. Thompson's recollection in Mr. Patterson's book. Mr. Schenkel won the toss and chose the second half, giving Mr. Thompson the job for the overtime period. In a statement yesterday, Gov. Robert L. Ehrlich Jr. said: "'Go to war, Miss Agnes!' and 'Ain't the beer cold!' are phrases that will live with the generation that experienced one of the greatest sports announcers of all time. Our hearts go out to Betty and the entire Thompson family." A memorial Mass will be celebrated Thursday at 11 a.m. at Cathedral of Mary Our Queen, 5200 N. Charles St. A private funeral is planned, and there will be no public viewing. In addition to his wife - whom he married in 1989 - and son, survivors include a daughter, Susan Perkins, and eight grandchildren. Mr. Thompson's first wife, Rose, died in 1985. Their daughter, Sandy Kuckler, died of breast cancer in 2001. Sun staff writers Laura Cadiz, Christian Ewell, Bill Free, Mike Klingaman and Roch Kubatko contributed to this article. |