Witness to Boston Blasts:

Frank Shorter, Marathon Legend and

NBC Commentator, Saw Munich Tragedies Too

by Joe Rubino, Daily Camera, Boulder, CO

(Special thanks to Lynn Petronella, a pioneer in women's running, for sending the ASA this article)

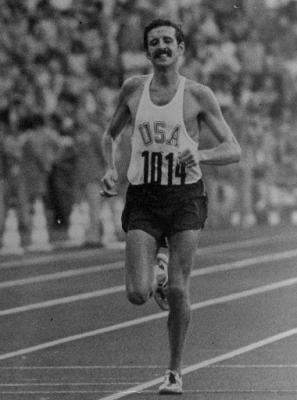

Frank Shorter crosses the finish line at the Munich Olympic stadium at the 1972 Olympics to win the gold medal in the marathon. (GK)

April 17, 2013 - In the summer of 1972, when Frank Shorter was representing the U.S.A. in the Munich Olympics, his room in the athletes' village was about 150 yards from the dorm where Arab terrorists kidnapped 11 Israeli athletes.

Alerted to the evolving news on TV, he looked out his window and saw terrorists with machine guns on the balcony. The terrorists and 11 athletes would all later die in a failed ambush at the airport. The event stands as one of the worst tragedies in modern athletic history.

On Monday, more than 40 years after Munich, Shorter was working for NBC Sports as a commentator at the Boston Marathon.

Shorter, 65-- who won the gold medal in the marathon that year in Munich and is credited with boosting the American running movement -- was walking into a store in downtown Boston, taking a shortcut on his way to a broadcast truck, when the first of two bombs went off.

The explosion rocked the large crowds gathered near the finish line. A few moments later, the second bomb went off, just 40 feet away from the vestibule where Shorter was standing.

"Unfortunately, I guess, I've had the experience in this situation that my thought process went right to the conclusion that it was a bomb," Shorter said of hearing the first explosion. "Then, I thought, 'Oh, my goodness. Anyone close to this ... there are going to be fatalities here."

Shorter made his way through the store and eventually to the broadcast trucks, near the race

tents. Despite the shocking nature of the event, Shorter said he saw many people react with levelheadedness and compassion, from public safety officials to onlookers to racers.

"I walked by people being triaged and being loaded into ambulances," Shorter said. "There were people who were very upset and other people who were comforting them. It was almost like this me-first attitude was being suspended.

"I did not see one person who seemed confused or in a state of panic or who did not know what to do. It was like everyone made a decision, whether through instinct or training, and they did it."

Shorter's own instincts told him that because he was not a trained first responder, the best thing he could do was get to a safe place. He walked to the Fairmont Copley Plaza, his hotel that also served as the race's headquarters.

"You don't think; you just react, and I think my reaction was that of an athlete," he said. "For me, the reaction is movement. Keep trying to find safer and safer ground."

It wasn't until he got back to the hotel that he started to ponder the "what ifs." What if he hadn't been running late to his meeting at the NBC truck and hadn't tried to save time cutting through the store?

He also thought about how an iconic American event, the Boston Marathon, which he had run five times and covered for local TV station WBZ another 22 times, would be changed by the tragedy.

"I had been there so many times. I was very familiar with the whole layout of the area," he said. "I think that is what makes it even more extreme in a way. It's an environment you're very comfortable in, and then suddenly it's never the same. Everyone will view that finish line in a different way."

Back in 1972, Shorter refused to let fear stop him. On the last day of the Games, he won the gold medal in the marathon, the first U.S. marathoner to win gold since 1908.

While he was able to return to Boulder on Monday night and think about the tragedy, Shorter admits he is still reeling from the shock of it, and he knows he and many, many others will need to time to process what happened.

He said he feels that giving in to fear -- both after Munich and Boston -- would only prove the perpetrators had succeeded in their quest to terrorize.

He hopes the rest of the running community feels the same.

Shorter said he hopes people will turn out for the Bolder Boulder 10K this year and marathons around the world, and he hopes the finish line of the Boston Marathon is in the same place next year as a sign that fear has not won.

"Part of the process of emerging from the shock and dealing with terrorism is returning to work on the things you can control," he said.

"Don't give anyone, no matter who it is, the satisfaction of reacting to what they have done out of fear or fear of what might happen."

* * *