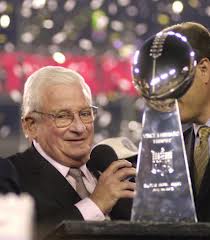

Art Modell, former Browns & Ravens Owner, Dies

September 7, 2012 — Art Modell's fingerprints can still be found all over the NFL. In Baltimore. In Cleveland. On Monday night football. On past labor agreements.

Along with colleagues named Rozelle, Halas, Brown and Rooney — all pillars of a fledgling league — Modell helped transform the NFL into America's preeminent sport.

Modell, former owner of the Cleveland Browns who moved his team, which became the Baltimore Ravens, died early Thursday. He was 87.

David Modell said he and his brother, John, were at their father's side when he "died peacefully of natural causes."

"The game of football lost one of its all-time greats," Detroit Lions owner William Clay Ford Sr. said. "Art's contributions to the NFL during his five decades in the game are immeasurable. I believe that Art did as much as any owner to help make the NFL what it is today. Art was a pioneer, a visionary and a selfless owner who always saw the big picture and did the right thing.

"Our game would not be what it is today if it weren't for Art Modell."

Modell spent 43 years as an NFL owner, overseeing the Browns from 1961 until he moved the team to Baltimore in 1996. Hel served as league president from 1967-69, helped finalize the first collective bargaining agreement with the players in 1968 and was the point man for the NFL's lucrative contracts with television networks.

Long before his Ravens won the Vince Lombardi Trophy in 2001, Modell teamed with Lombardi, commissioner Pete Rozelle and others to lay the foundation for the league's success.

"Art Modell was a most influential member of commissioner Rozelle's 'Kitchen Cabinet' for many years, along with Dan Rooney and the late Tex Schramm," said Joe Browne, the longest-tenured player in the league's front office. "Ironically, Art is the only member of that group who is not enshrined in Canton. Hopefully, the Hall of Fame media selectors will rectify that oversight in the near future — not as an emotional reaction to Art's death, but as a rightful reflection of his longtime contributions to the NFL."

NFL commissioner Roger Goodell praised Modell's work within the league as it was gaining momentum a half century ago.

"Art Modell's leadership was an important part of the NFL's success during the league's explosive growth during the 1960s and beyond," Goodell said in a statement. "Art was a visionary who understood the critical role that mass viewing of NFL games on broadcast television could play in growing the NFL."

But Modell's reputation took a hit from which it could not recover when he pulled the Browns out of Cleveland following a round of secret negotiations with Baltimore city officials. The move was made not because of poor attendance in Cleveland, but because Baltimore provided him with a better business opportunity.

It's widely believed that the move is the main reason Modell died without gaining entry into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He was a pariah in Cleveland and a hero in Baltimore.

When the Colts left Baltimore for Indianapolis in 1984, Baltimore went 12 years pining for another team. After the Browns left, Cleveland got an expansion team, a new stadium and retained its team colors and history, thanks in no small part to Modell.

But from the day he left to the day he died, he never got much love from the city he left behind.

"I have a great legacy, tarnished somewhat by the move," he said in 1999. "The politicians and the bureaucrats saw fit to cover their own rear ends by blaming it on me."

Browns fans became even angrier after Modell's team won his only Super Bowl.

"If Art could have given the trophy to Cleveland, I believe he would have," former Browns coach Sam Ratigliano said. After that Super Bowl win, Modell did a little dance as part of an agreement with linebacker Ray Lewis, the second player selected by the Ravens in their inaugural draft in 1996. Lewis considers that moment to be among his most memorable during his 17-year relationship with a man he considered to be an owner in name only.

"Us on that stage, I told him that if we win it, he's going to have to try to do my dance," Lewis recalled Thursday, his voice cracking with emotion during a somber day at the team complex in Owings Mills. "We got on stage and he did the dance. It capped off exactly the way it was supposed to end. We were able to bring him what his true dream was, the Lombardi Trophy."

Brian Billick, coach of that Super Bowl team, said of Modell: "It was a joy to come to work for him. He accomplished so much as an owner: championships, playoffs, the TV contracts, the leadership in the NFL. They are all great and deserving of the Hall of Fame. Those who worked with Art will all say the same thing. He was a Hall of Fame person."

Modell's Browns were among the best teams of the 1960s, led for a time by sensational running back Jim Brown. Cleveland won the NFL championship in 1964 — Modell's only title with the Browns — and played in the title game in 1965, 1968 and 1969.

But his early years with Cleveland also were marked by controversy when he fired the team's only coach to that point, Hall of Famer Paul Brown, after the 1962 season. Brown then went on to co-found and coach the Cincinnati Bengals.

Modell said he lost millions of dollars operating the Browns in Cleveland and cited the state of Maryland's financial package, including construction of a $200 million stadium, as his reasons for leaving Ohio.

"This has been a very, very tough road for my family and me," Modell said at the time of the Browns move. "I leave my heart and part of my soul in Cleveland. But frankly, it came down to a simple proposition: I had no choice."

Some NFL owners have several other sources of income. Modell had his football team. Period. And although the move to Baltimore helped keep him afloat for a while, he ultimately had to broker a deal that made Steve Bisciotti a minority owner. Part of the arrangement was that Bisciotti could assume majority ownership, and that's what happened in April 2004.

Bisciotti has since poured millions into the team, financing construction of a lavish practice facility in Owings Mills, Md. As a tribute, Bisciotti insisted that a huge oil painting of Modell be hung above the fireplace at the entrance to the complex.

Modell had an open invitation to come to camp, and although his health was failing in recent years, he occasionally dropped by to watch practice, going around the field in a golf cart.

Lewis never failed to come by and say hello, and their relationship was so tight that they spent a few emotional moments together Wednesday in the hospital.

"The things that I shared in his ear, I will also keep that between me and him because it's like a son and a father," Lewis said. "I loved the man dearly."

Born June 23, 1925, in Brooklyn, N.Y., Modell dropped out of high school at age 15 and worked in the Brooklyn Navy Yard cleaning out the hulls of ships to help out his financially strapped family after the death of his father.

He completed high school in night class, joined the Air Force in 1943, and then enrolled in a television school after World War II. He used that education to produce one of the first regular daytime television programs before moving into the advertising business in 1954.

A group of friends led by Modell purchased the Browns in 1961 for $4 million — a figure he called "totally excessive."

"You get few chances like this," he said at the time. "To take advantage of the opportunity, you must have money and friends with more."

Modell's work as a civic leader included serving on the board of directors of several companies, including the Ohio Bell Telephone Co., Higbee Co. and 20th Century-Fox Film Corp.

Modell and his wife, Patricia, continued their charity work in Baltimore, donating millions to The Seed School of Maryland, a boarding school for disadvantaged youths; Johns Hopkins Hospital; and the Kennedy Krieger Institute. The couple also gave $3.5 million to the Lyric, which was renamed the Patricia & Art Modell Performing Arts Center at The Lyric.

Patricia, his wife of 42 years, died last year.

Besides his two sons, Modell is survived by six grandchildren.

Associated Press